CONSENSUS DESIGN PROCESS

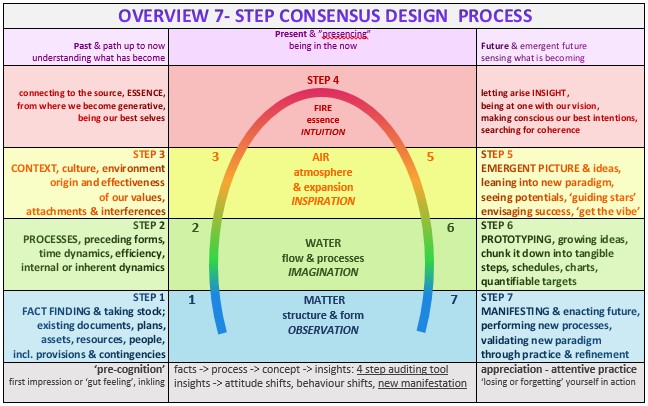

The consensus design process is the result of the collaboration between Dr Margaret Colquhoun and Prof Christopher Day in the 1990’s, bringing together a Goethean scientific method with action research for sustainable development. It builds on insights from natural science, social science and spiritual science, to enable a holistic approach to phenomena as evolving living organisms.

The process can be applied in full and run in cyclical patterns to achieve regenerative sustainability (7-steps on annual or reoccurring cycle), be used project specific for individual outcomes (one-off targeted) or be only applied in parts as auditing tool (steps 1- 4 only).

It can be framed by two further steps, a pre-cognitive, intuitive grasp of the initial situation (whilst not rationalised, this often shows striking resemblance to later methodical findings) and a post completion review (to trace systematically real life performance).

1: Facts: ‘taking stock’, assets, development plans and other strategic documents, i.e. existing assets & resources of the organisation.

2: Processes: life cycles, progress with plans, transitions & time dynamics, i.e. efficiency of strategies and policies in use.

3: Context & culture: sensing the dynamics, motivations or tensions that induce or drive change, i.e. effectiveness of our values in practice.

4: Essential task now, my relationship and responsibility to the whole, connecting to the source from where I become generative,

5: Inspiration/ apprehending new ideas: gesture and direction of renewal, seeing synergies & relationships, emergent future in context.

6: Taking form/ prototyping: growing ideas into matter, expanding the imagination, translating change picture into actions & plans.

7: New Manifestation: new forms in practice, working with and from the new paradigm or newly created situation, acting on the future.

Blogs and Articles

Related practices:

Consensus design found wide resonance with urban phenomenology, eco-architecture, Goetheanism, Anthroposophical medicine, Waldorf pedagogy, Camphill and holistic social sciences at the turn of the millennium.

From there it found entry into organisational management and leadership trainings, pioneered by Otto Scharmer as Theory-U, in collaboration with the Presencing Institute at MIT and since 2012 it is also integral to the programmes of the GNH Institute in Buthan.

The UN adopted it into the global strategy for ‘Well-being and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm’ and commissioned a World Happiness Report including a GNH Index, which gets regularly updated.

In the sustainability sector it is often referred to as co-creative practice and viewed as a holistic pathway to systemic change and transformational leadership.

Within the Anthroposophic framework it can be referenced back to Steiner’s concepts of Three-foldness (integrating body, soul and spirit), Four-foldness (four elements and realms) and 12-foldness (wholeness). The seven steps can be related to the seven life processes and some organisations derive from it seven archetypal care qualities.

Holistic approach to care

It is increasingly recognised that long-term illness and speed of recovery are deeply linked to our inner state of health and wellbeing. Whilst medicine and therapy take the lead in curing, the physical environment, architecture and ambience vastly influence the patient’s sense of ease and trust in the healing process.

An ambience of natural materials, natural light, vistas into gardens and nature, a delicate sense of beauty and harmony in the proportions of spaces and attention to detail with subtle colour schemes, exude balance and care. We mirror inside what we experience outside and disease is what occurs when the healthy flow of regenerative forces is compromised. Hence good orientation and flow between spaces and a sense of interconnectedness of the internal and external features all contribute to the “therapeutic approach” in care environments.

With mental health issues on the rise, triggered by an overdose of polarising stimuli, there is a need to pay renewed attention to the more subtle nuances of sensory experiences.

Over the years we have consulted on many project from individual therapy spaces to whole therapy centres to collaborate with therapist and clients in the development of sensitive architecture that enables, rather than constraints our sense of wellbeing. We work with a Steiner based approach, incorporating the concept of the 12 senses and four classical elements, to broaden and harmonise sensorial experiences within the built environments.

Whether it is a water feature in a courtyard, space evaluation for sensory experiences, or more principle design considerations for the overall layout and landscape integration, we have consulted on many projects in the care sector to create the best possible experience for patients, staff and carers.

Rudolf Steiner – Towards an organic architecture

The field of organic architecture is broad, with a heritage going back to megalithic times. There are diverse interpretations of what constitutes an organic approach to architecture and the most beautiful examples are often sacred sites and ceremonial architecture. In general architecture serves to protect ourselves against the natural environment, but the finer examples go beyond protection and actually integrate ourselves more fully in the environment. This drive towards greater re-integration and connectedness to the natural world has rekindled the interest in organic architecture.

Today’s rationalised worldview looks at contemporary architecture mainly from a functional point of view, with an emphasis on efficiency. But some clients and architects view the integration of human needs within the natural environment as a broader function and purpose of human existence. The attempt to articulate and build a more symbiotic relationship with the environment can lead us into the field of organic design, where there is a whole canon of form principles, geometric relationships, processes towards the use of local and natural materials, including cascading and circular resource cycles, all closely derived from nature and bio-mimicry.

At the turn of the 20th century, organic architecture was a much-discussed topic in many stylistic streams, from the Arts and Crafts movement to the modernists. Similar tensions exist today, with the debate ranging from social ecology, to sustainability and carbon neutral living for the 21st century.

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), a prolific philosopher of the early 20th century, continues to find interest amongst those concerned with a holistic approach to design and sustainable living. His teachings touch an almost all areas of life and have found widespread application in biodynamic agriculture, homeopathic medicine, Steiner Waldorf Schools and innumerable Anthroposophical organisations.

Not so well known are his thoughts on the arts and architecture, as a synthesis of the arts. Due to the philosophical nature of the subject, little scientific research has been undertaken to explore his architectural indications more systematically.

A German publication by Espen Tharaldsen “die verwandlung des alltags” (Verlag Freies Geistesleben, 2012) gives a very good synopsis of Steiner’s architectural impulse and its interpretations internationally. It contextualises the way his thoughts on art and architecture have been applied over the course of the 20th century and illustrates the possibilities and limitations of Steiner’s architectural legacy for the 21st century.

It clarifies, there is no such thing as Anthroposophical or Steiner architecture as a historic style. But there are examples of organic architecture created by individuals, who work out of Steiner’s philosophy and appreciate the world as ‘wholeness’, a unity of physical needs and cultural evolution, encompassing even metaphysical dimensions. Buildings designed from that level of consciousness reflect in their forms, functions and conception the idea of wholeness, expressed through the means of their time. This search for a unifying interconnectedness informs the approach for organic or biophilic design in our practice.

Steiner emphasises to express not just the functions (form follows function), but also the quality of relationships through architecture, adding a profoundly human dimension that imbues architecture with our personal and collective humanity. Architecture appears then less as a stylistic object, but as an ordering principle for social integration and productivity.

This approach resonate strongly with co-housing and life sharing communities, who understand architecture primarily as a community building tool, not as investment vehicle, adding a whole layer of social value and purpose to the actual built environment. In this context the conception of the social architecture precedes the physical architecture. The strength of our practice has been to facilitate design processes that help clients to do both, develop their social ecology and their built environment simultaneously.

In the UK there has been a small forum for members and friends of the IFMA (Internationales Forum Mensch und Architektur) for anyone interested in the subject. Since 2012 the so called ‘Architecture Steiner’ group has organised and facilitated numerous seminars, workshops, study trips and international exhibitions dedicated to the evolving dialogue around organic architecture inspired by Steiner’s ideas.

For further information see also IFMA magazine: https://m-arc.org/de/

Dr Margaret Colquhoun’s legacy in holistic Science

Introduction:

Dr. Margaret Colquhoun (1947-2017) was a Goethean scientist, who explored the synthesis of natural science and art as an integrated way of knowing. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) had considered the relationship of aesthetics and science in his exchange with Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805) as early as 1794 and to this day Goethe’s world view challenges the prevailing paradigms of the 19th and 20th century, which strictly separates scientific research from aesthetic expression, the actual appearance. This keeps the emphasis of science on probability and lawfulness as fixed system, rather than a methodical exploration of phenomena; as morphological manifestations of natural lawfulness capable of transformation. Margaret’s work focussed on the qualitative expression of natural phenomena, she rejected hasty, categorical answers or explanations and saw the scientific and artistic investigation into the inherent nature of natural phenomena as more important than the proof of specific aspects and properties. Her question was not just: what can be seen? (with the eye or the microscope down to the molecular level), but what does it mean in the context of the phenomena?

The search for meaning enabled her to never lose sight of the human intentionality in scientific research, the ethics of enquiry and the purpose of results in the circle of life.

We can observe, that Margaret’s strive toward a holistic world view became more and more evident in the course of her own biography and motivated her to leave behind academia and conventions for a life rooted in a holistic practice in the service of nature, enabling her to explore the unity and wholeness of science and art.

Biographical sketch

Margaret Colquhoun, ne Kelsey, was born in 1947 in Ripon, North Yorkshire, where she and her brother enjoyed a well-supported upbringing. Given her academic aptitude she enrolled in 1965 at Edinburgh University, where agricultural science, zoology and population genetics were part of her undergraduate studies. She continued her studies as research associate under Professor Conrad Waddington in the department of zoology and attained a doctorate in evolutionary biology in 1978 (1). During her years at Edinburgh University she came into contact with world class mountaineers including (later Sir) Chris Bonnington, Mike Galbraith, Doug Scott and David Bathgate, to whom she was married between 1970-1977 and with whom she remained close friends with throughout her life. Margaret joined the British expedition to Mount Everest in 1972, tracking to base camp, collecting specimen for the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh.

In the late 1970’s Margaret took great interest in the work of the Philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) and the various fields of work within the Anthroposophic movement worldwide. This brought her into contact with curative education in Austria and shifted her focus from purely scientific research to a wider picture of natural science, as ‘life science’ in a broader sense. From 1980 she became involved in social enterprises around Edinburgh, such as Helios Fountain and other alternative organisations, looking for practical application of holistic ideas.

In 1982 she suffered a head injury during a fall and the ensuing recovery at Park Attwood Clinic in Worcestershire heightened her appreciation for holistic Anthroposophical medicine. She met Dr James Dyson and Dr Michael Evans, both of whom would later become research colleagues in medicinal plant studies at the Anthroposophical Medical training hosted at Emerson Collage.

Holistic Science

Inspired by the possibility of an alternative view on science, Margaret relocated in 1984 to Germany, where she undertook three years of training and research at the Carl Gustav Carus Institute in Öschlbronn under its director Tomas Goebel. Goebel introduced her to the Goethean Scientific method and tasked her to undertake a significant piece of research on the Buttercup family. Through her work under Goebel she came to a new appreciation of Goethe (1749-1832) as scientist and artist, often viewed as ‘universal genius,’ who had influenced central European thought decades beyond his time.

Goethe’s world view and his ideas on archetype and metamorphosis remained a constant in Margaret’s life and became an inspiration for her work. It opened up the possibility for scientific enquiry to go beyond fact finding into an imaginative process of apprehending the essential nature of the phenomena, and leads our sense perception through the rigour of scientific enquiry to an archetypal truth, capable of appearance in various forms.

In 1987 Margaret transferred to the Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum, in Dornach, Switzerland, under its director Jochen Bockemühl (1928 – 2020). Bockemühl was working on landscape research and took Margaret’s interest in plant study into a broader context of plant communities, ecosystems, landscape restoration and regeneration. His findings are well documented in numerous publication, and his book “Awakening to Landscape” (2) became a reference point for many of Margaret’s Landscape courses. One of the core messages is to view landscape neither as wilderness nor manmade landscape, but as nature’s reflection of the evolution of human consciousness.

Research and Publications

When Margaret returned to Scotland in 1988 she felt equipped with a new approach, the Goethean Scientific Method and was determined to put it into practice in Scotland. It felt like she had new eyes for the world around her and she organised numerous field trips all over Scotland for study projects. This gave momentum to the foundation of The Life Science Trust in 1992 for the furtherance of Goethean Science and Art, which became the umbrella organisation for all her future courses, research and consultancy work. Margaret frequently collaborated with artists and scientists and saw collaborative work as an essential part of her Goethean approach. A joint publication with the artist Axel Ewald followed in 1996, “New Eyes for Plants” (3). It is a practical workbook that portrayed some of the insight and findings gained in the Life Science Seminar, with a foreword by Brian Goodwin.

In order to anchor her work, a specific place was needed to establish a teaching centre and Margaret set her eye on a site on the edge of the Lammermuir Hills in south east Scotland. In close collaboration with the architect and environmentalist Christopher Day MBE, work started on a master plan for The Pishwanton Goethean Science and Art Centre.

In his book ‘Consensus Design’ Christopher Day recalls the transformative collaboration between Margaret’s Goethean Science landscape study and his own participatory architectural work.

“In 1991 Margaret and I met for the first time. We had both heard about each other’s methods and had much to discuss. We agreed that her approach –studying a place up until the present- was really only half a process, as was mine, -developing a place, which means changing it from how it now is.

We decided, therefore to try and work together, her phase of studying leading into mine of design- and with a structure whereby the design process would mirror the study process.

We chose a hypothetical project: a Goethean Science Centre and a place about 60 acres of woods, grassland and mash in Southeast Scotland. We completely underestimated the power of this process to bring a vague dream of a possibility into reality.”

(4) Christopher day, Conesus design, Chapter 11, P91.

We can see how Margaret’s Goethean Scientific Method and Christopher Day’s participatory design approach complemented each other, her landscape study and his ecological design distillation achieved a synthesis for holistic place making.

During that time Margaret maintained regular exchanges with Brian Goodwin, with whom she shared the view that natural science must seek to explore and explain natural phenomena as living phenomena, not as dead matter. Brian visited the Pishwnaton project on several occasions, actively contributed to courses such as “Beholding the Heart of Nature” and a tree was planted in his honour in the central garden in 2009 to commemorate his support for the work at The Life Science Trust.

Since the early 2000’s Pishwanton had become synonymous with pioneering eco architecture and holistic land care practices with courses running on Biodynamic agriculture, Herbology, Forest gardening, art residencies, Goethean science and plant study. Influential courses were: The Life Science Seminar, the New Hibernian Way and “Beholding the Heart of Nature”, which attracted students from all over the world to Pishwanton.

Margaret was advocating an integration of science and art in all development aspects of the Pishwanton project, from land management to architecture, from education to therapeutic activities, bringing not only scientific knowledge but also human consciousness to all life cycles. This highlighted the human influence on natural phenomena, magnified in scale by the compounding evidence of the devastation our current consumer culture imposes on the larger ecology of life, from dying habitats, to mass extinction of species to widespread human suffering.

Revealing the inherent potential in nature to heal itself, requires the human being to address and transform their own nature. Not by manipulating it into something other, but by becoming fully conscious of it and its effects. This leads to a morphological picture of all life development and can enable a glimpse into the complex accomplishment of nature and its evolutionary potential as a living organism.

In a lectures give at a conference on architecture and wholeness at Emerson College in 2013, Margaret portrayed, how her view on natural science builds on Aristotle’s concept of Entelechy, namely the appearance of that, which is realised or made actual that which is otherwise merely potential. She believed that the ultimate potential of nature is to be imbued with consciousness through human interaction and only through the conscious cultivation of this relationship will the earth as living organism achieve its ultimate realisation.

Over the years, Margaret was a guest teacher at Emerson College, Schumacher College, the Scottish Institute of Herbal Medicine, Steiner Schools, Camphill Communities, Findhorn Foundation, Biodynamic Association and numerous environmental programmes. She remained locally very active through the Pishwanton Project, collaborated with the John Muir Trust and local schools and led many outdoor learning provisions.

Conclusion

Individuals who came into contact with Margaret felt that she awakened in them the awareness and desire for a holistic view of nature and mankind. It was not just the study and themes of her courses, but her commitment to methodology that enabled people to take her approach further. Students learned to trust their own observations and insights and to transpose the Goethean approach into their own field of interest.

At a time, where much focus is put on promoting ideas, Margaret walked the talk, she rooted holistic science in daily practice and a big part of that story was the establishment of the Life Science Project at Pishwanton. It was proof, that a holistic approach to all aspects of life was possible, even if at times challenging.

Reflecting on Margaret’s research motivation, Iddo Oberski, former lecturer at the Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, recalls:

“My impression was that Margaret was deeply interested in creating a sanctuary for both nature and the human being, where both could meet on equal footing. This entailed on the one hand establishing a location where through holistic science nature could be present at her best, on the other hand facilitating each human being to also show up at their best in the presence of nature and other human beings. So it was about human transformation through deep encounters with nature, each other and oneself, using Goethean Science as a shared language or medium so to speak. “(5)

Margaret was a spiritual person and Christianity was a guiding principle in her private life, which brought an ethical dimension and reverence for nature to her work. In her final days, she expressed her thoughts on ‘Pishwanton as a sanctuary’ as “a place, where one can discover the divine in nature and in each other”. (6)

We see here similarities to contemporaries such as Henryk Skolimowski, who articulated the need for a shift in scientific and societal paradigms. He was philosopher in residence at Dartington Hall and in later years Chair of Ecological Philosophy at the University of Lodz, Poland (1992-97). Margaret was influenced by his work and many ideas outlined in his book “A Sacred Place to Dwell” (7) were put into actual practice at the Goethean Science Centre.

The qualities and principles of the seven step Goethean approach have been further developed as transformative practice applied to various fields, such as management, leadership and social renewal as can be seen with ‘Theory-U’ by Otto Scharmer, MIT. What has become apparent during the 21st century is that our future on earth depends more and more on the interior condition of each individual and our ability to find a way to sense into the essence or source of life. Margaret took this very much to heart and she concluded in her book New Eyes for Plants: “We are all artists (of life) and we are all scientists (in life). The art or science of being human is to find a balance between these two inherent tendencies within us.” (Page 173)

Margaret strove to awaken in the scientist an artistic, creative imagination that looks toward the realisation of inherent potential and to stimulate in the artist a deep quest for truth or revelation. From that perspective, science and art unite in wisdom and as individuals we can feel compelled to attain wisdom that integrates us into the living organism of the world.

Her contribution to holistic science is her commitment to further the Goethean practice, which she identified as one way to conduct research into the essence and meaning of natural phenomena without severing ourselves from nature.

Finding purpose and harmony with nature was her definition of mastery, her key to co-creating with nature and an expression of mankind’s endeavour to knowingly act as intrinsic part in the ecology of life on earth, consciously partaking in its future evolution.

Endnotes

Dyson James,2017, Margaret Colquhoun Obituary, Archive Pishwanton

Bockemühl Jochen, 1992, Awakening to Landscape, Goetheanum

Colquhoun Margaret, Ewald Axel, 1996, New Eyes for Plants, Hawthorn Press, Stroud

Day Christopher, 2003, Conesus design, Architectural Press, Chapter 11, P91.

Oberski Iddo, 2021, email consultation, Edinburgh

Colquhoun Margaret, 2017, Sanctuary Notes, Archive, Pishwanton

Skolimowski Henryk , 1993, A Sacred Place to Dwell, Element Books, Dorset

Scharmer Otto, 2007, Theory-U, Cambridge, MA

Colquhoun Margaret, Ewald Axel, 1996, New Eyes for Plants, Hawthorn Press, Stroud, Page 173

Design

Innovative architecture

Sustainable environments

Strategic development plans

Project management for charities

Client advice

Individual custom service

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Contact